Schedule a talk with one of our advisors to learn more about Summitry and how we can help you get a foothold on your financial life. For career opportunities please visit careers at Summitry.

Team

Insights

Pages

- Let's Talk

- Phone / Directions

Deferred Annuities, the Mets & Bobby Bonilla

Aug 5, 2020

The Worst Deal In Baseball

For most of us, July 1st marks the second half of the year. For Bobby Bonilla, it’s the best day of the year. He gets a check from the New York Mets for ~$1.19 million dollars. That might not be an impressive salary for a top-tier baseball player, but Bobby Bonilla hasn’t worn a Met’s uniform since 1999. He hasn’t even laced up his cleats since 2001. Despite being retired and 57 years old, Bonilla will keep receiving those checks until the year 2035.

Why would the Mets agree to such a ridiculous proposition, years after Bonilla left? The answer involves a smart accountant, a Ponzi scheme, and some really, really terrible financial planning.

Bobby Bonilla’s View of the Mound

Bobby Bonilla began his major league career with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1987, the season after the Mets won their last World Series. After an error-prone stint at third base, Bonilla moved to right field (informally, the position for one’s worst fielder) and hit his stride. He combined with a young Barry Bonds to drive the Pirates to two National League East championships. In the next several years, Bonilla would be named an all-star four times and develop a reputation as a solid slugger.

Bonilla’s first (yes, first) signing with the Mets in 1991 made him the highest-paid player in the league. Despite the high price tag, Bonilla put up lackluster performance for the next several years. His time was marked by a combative relationship with the press and a series of on and off-field antics. After a lackluster run, Bonilla ended his time with the Mets. Bonilla bounced from team to team as a free agent, never quite rekindling his status as an all-star hitter.

Undeterred by their first run with Bonilla, the (apparently masochistic) Mets decided to give him another shot. As you might imagine, it went no better than the first time. Bonilla openly argued with manager Bobby Valentine, requesting more playing time. He (reportedly) refused to play or pinch hit, often without explanation. When he did play, Bonilla failed to deliver any of the offensive might the Mets had hoped for. The culmination of bad blood was the sixth game of the 1999 National League Championship Series. Bonilla was notably absent and reportedly was occupied playing cards with his teammate, Rickey Henderson.

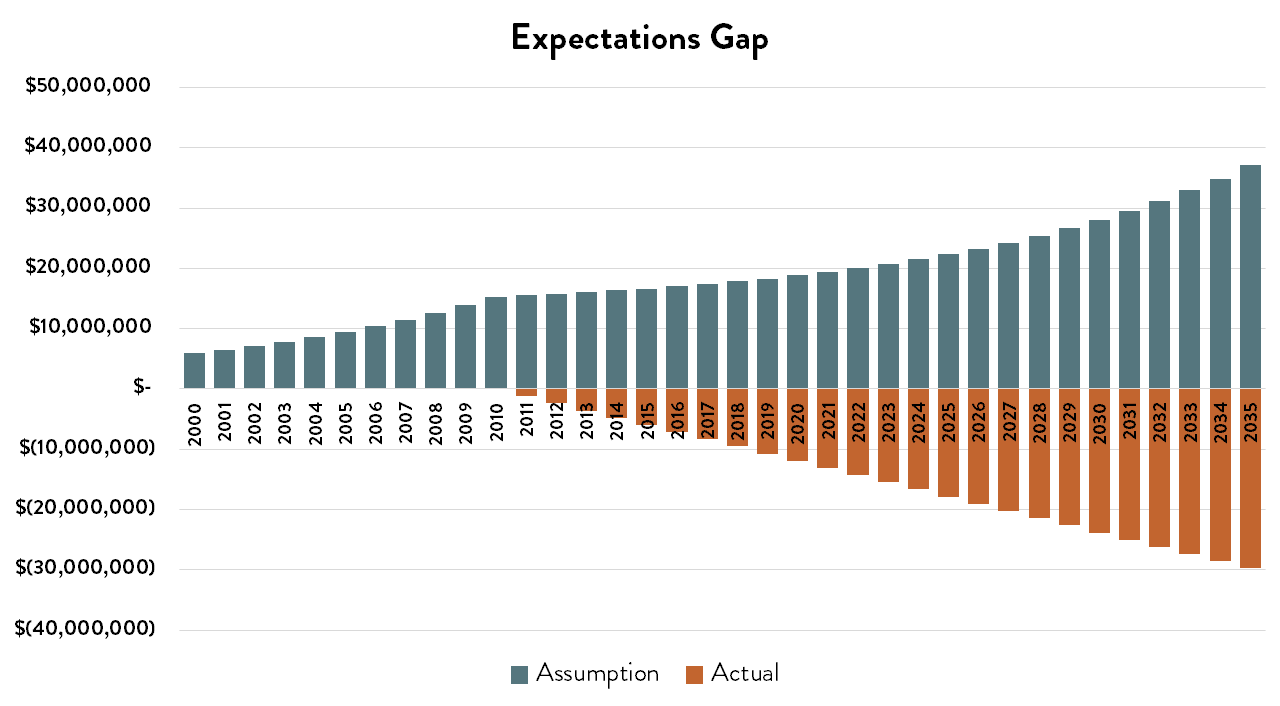

At this point, the Mets had thoroughly learned their lesson. They badly wanted to get rid of Bonilla, but were hamstrung by his contract. The Mets owed Bonilla a remaining ~$5.9 million, a sum that they would vastly prefer to spend on new talent. Accordingly, the Mets approached Bonilla with an offer – Bonilla would defer receiving any payment until 2011. In exchange, the Mets agreed to contract payments of ~$1.19 million every year until 2035.

You might recognize this payment structure, as it is simply a deferred annuity. As its name implies, a deferred annuity is a promise to receive payments in the future for a specified period of time. In the simplest form of this annuity, there is a guaranteed interest rate that determines the amount of the future payout. Bonilla’s accountant suggested a 10% rate, and the Mets pushed for 6%. Accordingly, they settled on a rate of 8%.

Even for a time of higher interest rates, a guaranteed return of 8% is surprisingly high. Why would the Mets agree to contract payments with such a high interest rate? They had access to one of the world’s premier money managers – Bernard Madoff. In fact, the New York Mets were one of Madoff’s largest clients. The logic of Fred Wilpon, the manager of the Mets, was as follows: if Madoff consistently makes 10%, and I only have to pay 8%, I’ll actually make money! Wilpon justified this as reasonable by projecting forward Madoff’s fraudulent historical returns.

The next part needs few details. As one of Madoff’s largest investors, the Mets also took some of the largest losses when his Ponzi scheme was exposed. Not only would the Mets not be able to meet their 10% return target, they lost a substantial amount of their principal as well. The Mets now found themselves in the uncomfortable position of having to honor a financial contract that was based on wildly incorrect assumptions.

Source: Summitry

Source: Summitry

The Dawn of Bobby Bonilla Day

Bonilla’s payout has been consistently ranked as one of the worst contract decisions of all time. Sports media honors “Bobby Bonilla Day” on July 1st, an unwelcome reminder for Mets management. However, let’s take a moment to acknowledge what the Mets actually did with the money they saved and perhaps provide a small amount of redemption. The Mets signed Mike Hampton, who went on to be the 2000 NLCS MVP as part of a World Series run. After the 2000 season, the Mets traded Mike Hampton to the Rockies for a pick that led to David Wright. Wright became one of the most prolific players in Mets history, chalking up team records for both stellar offense and defense. Maybe the Mets deserve a little more credit, even if they ended up pretty firmly on the wrong side of history.

What’s the takeaway? Despite being an amusing anecdote and a piece of sports history, Bonilla landed one of the most favorable deals in history despite a mediocre performance and little negotiating leverage. He did a few simple things right, all of which apply to the way we make financial decisions. Equally, the Mets made some serious mistakes that we can avoid.

Past Performance Is No Guarantee of Future Results

It is easy to make rosy predictions about the future that justify our decisions today. Setting aside the Madoff Ponzi scheme, a guaranteed 10% return is too good to be true. While it’s an excellent goal, a decision that is predicated on a 10% return being necessary is not a good decision. Planning is about acknowledging that the future may be different than the past and part of that process is allowing for a range of outcomes. Planning is about optimizing for the chances of success, not absolute performance.

This is an example of recency bias, a problem that affects both sports lovers and investors. We tend to project what has happened in the recent past into the future. In sports, this appears as the “hot-hand” fallacy, in which players on a hot streak are assumed to continue performing above-average. In investing, there are countless studies showing that funds flow to asset classes and managers that have recently outperformed. These tend to mean-revert and underperform in the coming periods, leading to subpar investor returns.

Thinking Long-term

From Bonilla’s perspective, he found himself with a party highly motivated to make a deal. Their focus was entirely on short-term optimization. Bonilla had already set aside a little nest egg and had no love for the Mets or Mets management. The Mets fell prey to another bias (bear with me on the name) known as hyperbolic discounting. Put simply, we prefer rewards to come now and consequences to come later. More importantly, this relationship is exponential — not linear — and leads to irrational decisions. Generally, carrying a credit card balance is an example of this phenomenon. Even though interest charges are substantial, there are a significant portion of people who choose to (not have to) carry a balance on their card. Rationally, most are aware that they will end up paying significantly more but choose to delay their payment (consequence) into the future, even though the cost is substantially higher the longer the payoff is delayed.

The Mets had run up their metaphorical credit card (salary cap) and needed to find some room to spend more money. Therefore, they were willing to forego short-term financial pain for an expensive future payout. From Bonilla’s perspective, he was more than happy to overcome this bias. Bonilla resisted the immediate reward, realizing the immense value he would receive in the future. With the passing of time, Bonilla has only looked more prescient:

“I just smile because I’m going to sit back, I’m going to take it day by day, and I’m going to have the last laugh.”

Bobby Bonilla

Enjoyed reading this article and want to chat more about investing or baseball? Or both? Contact us today!

All material of opinion reflects the judgment of the Advisor at this time and is subject to change. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation to buy, hold, or sell any financial instrument or investment advisory services.

GET THE NEXT SUMMITRY POST IN YOUR INBOX:

MORE INSIGHTS AND RESOURCES

Let's talk

Schedule a talk with one of our advisors to learn more about Summitry and how we can help you chart a path for your financial future.

Alex Katz

President