Schedule a talk with one of our advisors to learn more about Summitry and how we can help you get a foothold on your financial life. For career opportunities please visit careers at Summitry.

Team

Insights

Pages

- Let's Talk

- Phone / Directions

When Less is More: Why The Best Investments are Boring

Jun 18, 2020

Today, it seems as though everything happens at a faster pace. Constant notifications alert us to breaking news on our phones and instant text messages have replaced more personal, but slower, modes of communication like voice calls. Financial news offers an endless parade of experts and prognosticators opining on the markets and compelling us to act now. Under these pressures the idea of sticking to a five, ten or twenty-year plan seems unthinkable. This piece will advocate for a more deliberate pace when it comes to making investment decisions for one key reason, besides making an investor’s life more pleasant: It works!

“Lethargy bordering on sloth remains the cornerstone of our investment style”

-Warren Buffett, 1990 Letter to Shareholders

In the early 1990s, as Warren Buffett was becoming a household name for investors, he toured business schools and gave this advice: Students would be better off to have a punch card with 20 punches on it to govern a lifetime of investment decisions. Each decision would require a punch of the card, forcing the investor to take great care and, as Buffett said, “use them for the right things.” While this may seem impractical, Buffett argued that students “aren’t going to get 20 great ideas in their lifetime. They’re going to get five, or three, or seven, and they can get rich off five, or three, or seven. But what you can’t get rich doing is trying to get one every day.” Point well taken.

Many years ago, in the wake of the Great Depression, the Corporate Leaders Trust was created to put the ideas that Buffett later espoused to business school students to the test. The leverage, speculation, and subsequent devastation of the Great Depression was a formative experience for an entire generation. A group of investors thought they had the solution: never trade. This idea would have been heretical only a few years before. However, many believed that manic trading had contributed to the crash, and a logical response was to limit this kind of behavior. They also decided to avoid the “high-fliers” of the day (more on this later) and focus on slower, more predictable growth companies. What they did, while seemingly unremarkable, is create one of the most interesting “buy and hold” experiments of all time.

The Corporate Leaders Trust purchased thirty stocks with the idea that the trust would not make any trades and would dissolve in 2015 (it has since been extended). The practice of managing the Trust over the years was slightly more complicated than the stated goal of complete inactivity, as the trustees had to make decisions with respect to Trust holdings in cases of acquisitions, divestitures and liquidations along the way. Nevertheless, the spirit of the Trust’s charter was honored. In excluding financial stocks and the technology stocks of the day (one of the hottest stocks back then was the Radio Company of America, or RCA), the fund bought mostly blue-chip names. Some have fared well, such as Union Pacific and Procter and Gamble, and continue to be household names. Several had a number of good years, but have since fallen on hard times, such as Sears and Eastman Kodak. Others have been acquired, leading to one of the fund’s largest positions in Berkshire Hathaway, a result of Berkshire’s purchase of BNSF railroad.

The big question is – how did it work? Surprisingly well. While we don’t even have data for the S&P 500 going back to the fund’s inception, the fund has outperformed the S&P 500 and other broad market benchmarks over most long-term time frames, averaging roughly 10.5% annually. The fund has weathered several wars, a number of market crashes, and fourteen different presidents. Less (in terms of activity in investing) can be more.

So why does this matter? I think there are several lessons to learn from this accidental experiment in buying and holding for the long term: (1) More is less; (2) The best investments can be boring; (3) Have a plan.

More is Less

Most things in our life are characterized by a relationship between incremental effort and incremental results. Doing extra sets in the gym is directly correlated with becoming a little bit stronger each day. In the gym and in many other endeavors, more is more. In investing, the relationship between effort and outperformance is more complicated. Success in investing certainly requires effort, but much more, it requires discipline; the discipline to set up an investment program, as with the Corporate Leaders Trust, that should stand the test of time and stick with it, or the discipline to limit one’s decisions to the best few, as Buffett advocated (and practiced). Discipline is hard to maintain in markets that offer the opportunity every business day to buy or sell tens-of-thousands of stocks, funds and ETFs with the click of a mouse. But in general, with investing more is less. Often, finding the next stock to buy or sell is counterproductive, and it’s not even particularly satisfying.

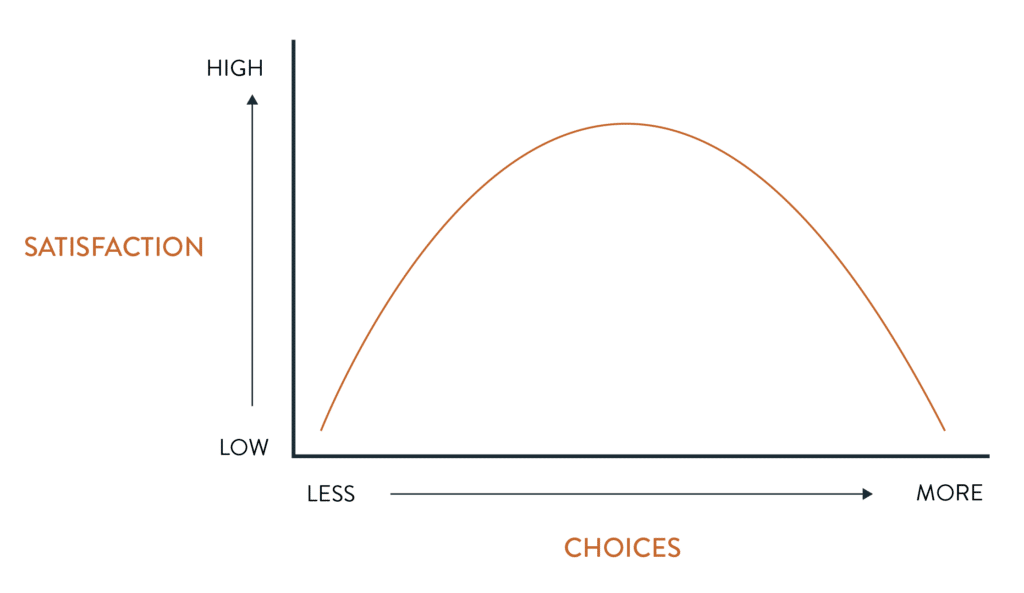

We suffer from a persistent state of overchoice – an inability to make a decision when confronted with too many options. When we have to make choices, our happiness generally is characterized by a U-shape: Investing in a way that optimizes for “Satisfaction” as well as results, we believe, is about finding a “sweet spot” in the middle of the “Choice” curve above – not too myopic, but not overextending oneself to the point of “analysis paralysis.” Investing is not about working harder, as we would in the gym, but it’s having the experience, skills, and prudence to know when it’s appropriate to act and when it’s appropriate to sit and wait.

Investing in a way that optimizes for “Satisfaction” as well as results, we believe, is about finding a “sweet spot” in the middle of the “Choice” curve above – not too myopic, but not overextending oneself to the point of “analysis paralysis.” Investing is not about working harder, as we would in the gym, but it’s having the experience, skills, and prudence to know when it’s appropriate to act and when it’s appropriate to sit and wait.

In essence, Buffett’s idea is closely tied to achieving that sweet spot. Not even the boldest investor would commit to one stock for the rest of their life, but not even the most adventurous would seriously consider trying to analyze all 40,000+ publicly traded companies.

The Best Investments Can Be Boring

One of the initial decisions in the Corporate Leaders Fund was to exclude the “hot” stocks, such as RCA. As RCA is now defunct (and its primary technology obsolete), it is hard to believe that this was as visionary a company in its time as some of the most popular companies of our days. However, eighty years from now, it’s likely that many of today’s most celebrated companies will be either obsolete or forced out of business by disruptors. This isn’t an admonition of any specific sector – however, in an age where technology has been the unquestioned driver of equity markets, it’s good to remember that the boring things (like railroads) can also be darn good investments over the long run. Sometimes the best investments are the least exciting – and the best companies can still make terrible investments if purchased at the wrong price. Broadly, we want to insulate ourselves from recency bias – the idea that we tend to project the recent past into the future. We don’t know what the next several decades hold, but it’s important to keep in mind that it’s the quality of the business and the price we pay that determines our return, no matter how boring.

Have a Plan

Perhaps the most important lesson to take away from the Corporate Leaders Trust is not in the fund itself, but how it was formed. The founders agreed on a set of principles that would guide the fund. They agreed, and put pen to paper, as how decisions would be made. This kind of discipline was likely gut-wrenching as a holding like Eastman Kodak slowly marched towards their demise (the fund did mandate a stock would be sold if its share price dropped below $1), but it also allowed the fund to benefit from the decades-long compounding of some of its successful holdings. That doesn’t mean you should buy thirty stocks for the rest of your life; few of us truly have such nerves of steel. Rather, you should have a plan that you agree to abide by through thick and thin, that reflects you, your circumstances, and your goals. It gives you something to anchor to in times of market volatility, and it serves as an important accountability measure. Whether you’re being accountable to yourself or you’re working with an advisor who helps keep you accountable, a plan allows you to keep a cool head when others are losing theirs.

Interested in learning more about our philosophy? Contact us today!

GET THE NEXT SUMMITRY POST IN YOUR INBOX:

MORE INSIGHTS AND RESOURCES

Let's talk

Schedule a talk with one of our advisors to learn more about Summitry and how we can help you chart a path for your financial future.

Alex Katz

President